Karate

Karate

Rare, Direct, Unbroken Lineage to the origins of Karate...

Traditional Karate Kata of the WKKJO Headquarters: SMAA

Under the Direction of

Simon Sherbourne 7th Dan (RHKKF), M.Ed

Simon Sherbourne 7th Dan (RHKKF), M.Ed

The Karate kata of the WKKJO are directly from Okinawa, Japan

and passed on from teacher to student (to our Founder who is a Direct Senior Student of Master Seikichi Odo [1926 - 2002]) over the last 300 years. The kata were developed so that techniques (waza) could be practiced in isolation with discretion as the ruling governments had banned any organized military training by locals. The fear was that the Okinawan people would organize and raise an army with the necessary skills for combat and eventually overthrow the imposed foreign governments from Japan and China.

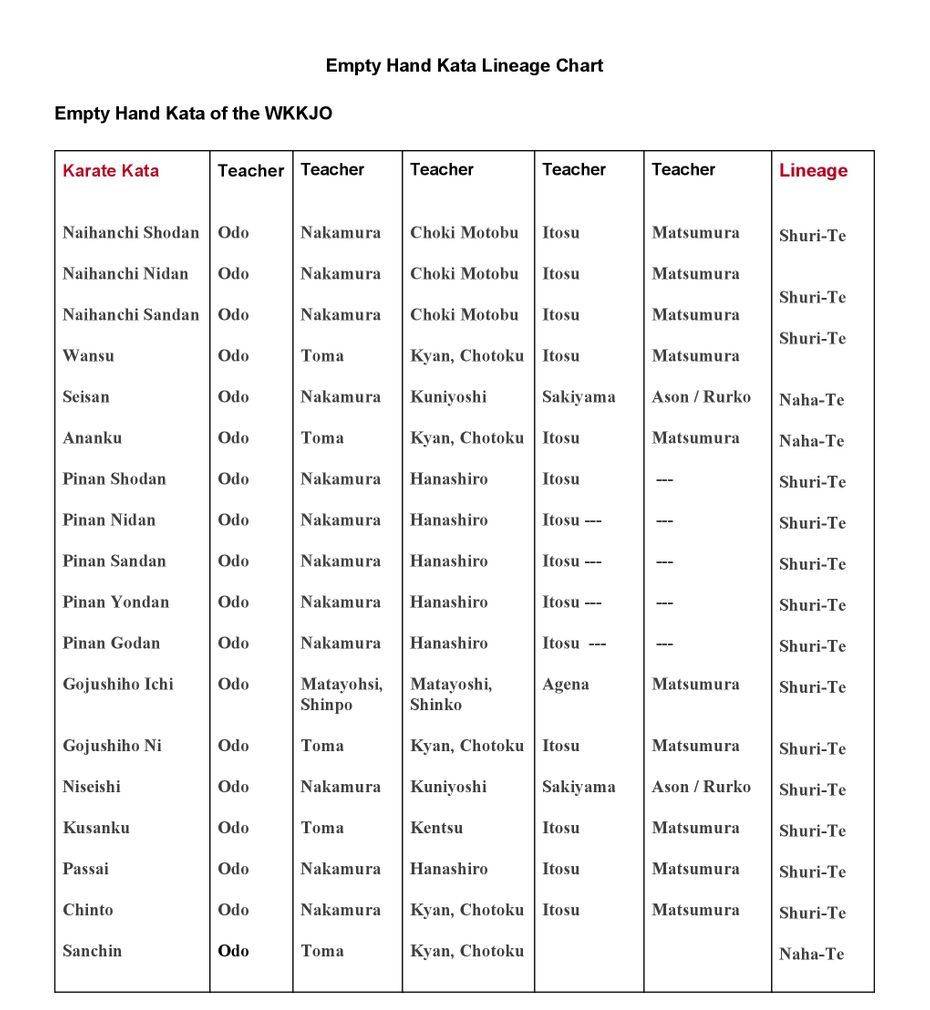

Traditional Karate Kata taught through the WKKJO

(Mostly of the Shuri-te lineage from Seikichi Odo of Okinawa)

Hakutsuru Ichi and Hakutsuru Ni were taught by Master Odo in the summer of 1994 along with Kobudo Kata: Chatanyara No Sai and Miazato No Tekkos Ichi and Ni (This totals 20 Empty Hand Kata taught by Master Seikichi Odo at the time of his passing in March, 2002).

Teachers who have passed on the Kata of the WKKJO:

Seikichi Odo, Shigeru Nakamura, Shinkichi Kuniyoshi, Seiki Toma, Chotoku Kyan, Shinpo Matayoshi, Chomo Hanashiro, Shinko Matayoshi, Yabu Kentsu, Anko Itosu, Sokon Matsumura, Karate Sakugawa

Karate Sakugawa: Sakugawa Kanga, 1733 - 1815), also Sakugawa Satunushi[1] and Tode Sakugawa,[1] was a Ryūkyūan martial arts master and major contributor to the development of Te, the precursor to modern Karate.

Sokon Matsumura was the senior student of Sakugawa Sensei. See Bushi Matsumura's (1800 - 1892?) story at: https://toshujutsu.wordpress.com/2014/06/30/sokon-matsumura-what-did-he-actually-teach/

Anko Itosu (1831- 1915)

Notable students of Itosu included Choyu Motobu (1857–1927), Choki Motobu (1870–1944), Yabu Kentsu (1866–1937), Chomo Hanashiro (1869–1945), Moden Yabiku (1880–1941), Kanken Toyama (1888–1966), Chotoku Kyan (1870–1945), Shinpan Shiroma (Gusukuma) (1890–1954), Anbun Tokuda (1886–1945), Kenwa Mabuni (1887–1952), and Chōshin Chibana (1885–1969).

Shinkichi Kuniyoshi (1848-1926) taught Shigeru Nakamura;

Chomo Hanashiro's (1869 - 1945 Shuri-Te lineage): Senior student was Shigeru Nakamura;

Shigeru Nakamura 1894 - 1969 - Okinawa Kenpo: was the primary teacher of Seikichi Odo;

Seikichi Odo (July 26, 1927 – March 24, 2002) Founder of the RHKKF (Ryukyu Hon Kenpo Kobujyutsu Federation) was the primary Karate and Kobudo teacher of Simon Sherbourne (November 22, 1967 - ) Founder and Director of the WKKJO.

It is well known that Odo Sensei had many Senior Students around the world. Sherbourne is one of them who chooses to carry on Odo Sensei’s teachings for the next generation of Budo-Ka through the WKKJO.

Seikichi Odo, Shigeru Nakamura, Shinkichi Kuniyoshi, Seiki Toma, Chotoku Kyan, Shinpo Matayoshi, Chomo Hanashiro, Shinko Matayoshi, Yabu Kentsu, Anko Itosu, Sokon Matsumura, Karate Sakugawa

Karate Sakugawa: Sakugawa Kanga, 1733 - 1815), also Sakugawa Satunushi[1] and Tode Sakugawa,[1] was a Ryūkyūan martial arts master and major contributor to the development of Te, the precursor to modern Karate.

Sokon Matsumura was the senior student of Sakugawa Sensei. See Bushi Matsumura's (1800 - 1892?) story at: https://toshujutsu.wordpress.com/2014/06/30/sokon-matsumura-what-did-he-actually-teach/

Anko Itosu (1831- 1915)

Notable students of Itosu included Choyu Motobu (1857–1927), Choki Motobu (1870–1944), Yabu Kentsu (1866–1937), Chomo Hanashiro (1869–1945), Moden Yabiku (1880–1941), Kanken Toyama (1888–1966), Chotoku Kyan (1870–1945), Shinpan Shiroma (Gusukuma) (1890–1954), Anbun Tokuda (1886–1945), Kenwa Mabuni (1887–1952), and Chōshin Chibana (1885–1969).

It is with Itosu Sensei

that we see a great proliferation of Okinawa's Karate...

Chomo Hanashiro's (1869 - 1945 Shuri-Te lineage): Senior student was Shigeru Nakamura;

Shigeru Nakamura 1894 - 1969 - Okinawa Kenpo: was the primary teacher of Seikichi Odo;

Seikichi Odo (July 26, 1927 – March 24, 2002) Founder of the RHKKF (Ryukyu Hon Kenpo Kobujyutsu Federation) was the primary Karate and Kobudo teacher of Simon Sherbourne (November 22, 1967 - ) Founder and Director of the WKKJO.

It is well known that Odo Sensei had many Senior Students around the world. Sherbourne is one of them who chooses to carry on Odo Sensei’s teachings for the next generation of Budo-Ka through the WKKJO.

What is Karate and Where did all the different styles of Karate come from?

Karate of old was simply called “Te” in Japanese, or “Ti” (sometimes spelled as “di”) in the older original language of Uchina (Okinawa). This was from the original “Toudi”, which meant “Chinese Hand” (Tou being a reference to the Tang dynasty in China), but the point is that there was only one “Te”. Even the naming of the 3 main branches of Karate (Suri-te, Tomari-te, and Naha-te) did not emerge until the 1920s or 30s when the masters had to come up with names when presenting the art to the Japanese. As I understand it, even these names were implemented to acknowledge each lineage with an identity (some would say that Naha-te did not even exist, and was created simply to appease Chojun Myagi and give his style of Goju Ryu some representation and back-lineage). This makes sense, given the fact that our Kata (RHKKF and the WKKJO) are primarily of the Shuri-te lineage, which is by far the main lineage and influence on modern-day Karate.

Choki Motobu and his views on Karate

Many think of him as a bad-ass (and for his time, he certainly was), but if you read his teachings it shows that he was dealing with the same noise over 100 years ago that we are dealing with today – and this is obvious in a great quote from Motobu: “Nothing is more harmful to the world than a martial art that is not effective in actual self-defense.” He was facing the same issues and dealing with the same types ineffective martial arts driven by ego rather than effectiveness that we deal with today. So he chose to challenge and test his technique, and his conclusions led him to take it back to simplicity – he stated many times that Naihanchi kata has everything a person needs to know (he viewed this Kata as a complete system of self-defense that could be studied for years). Despite what people think, Motobu did learn other Kata, but he chose to focus on Niahanchi sho-dan as his primary training tool – it was simple, brutal, effective, and it contains all of the key combative techniques in your list below.

Sherbourne's Discussions with a couple Karate Masters on the subject...

During my training with Hanshi Seikichi Odo (1987 to 2002) I asked these questions and Odo Sensei explained that all the existing upper ranks in Okinawa viewed karate as one complete martial art. He inferred to me that it was ego that spawned the birth of so many different styles, and that this was not in keeping with being a selfless Budo-ka/ Karate-ka.

I asked Seiki Toma (in 2002) the same question as to where did all the different styles of karate come from... He chuckled a little and said when he was a young man, all these different styles (Shotokan, Goju Ryu, Shito Ryu, Isshin Ryu, Kyokushin, Shorin Ryu... etc.) did not exist. Karate was just karate, and everyone on the Island (Okinawa) trained together and shared their practices with each other.

This perepective on training is far from the current state of karate practice that separates practitioners by style and variations of practice. Training for tournaments also causes practitioners to cator to the rules for scoring and defending, instead of training for the purposes of life threatening circumstances.

However, in traditional styles there still exist some fundamental combatives principles that transcend style:

1 - The “One Punch Finish” is a reality with proper karate training (Makiwara, etc.);

2 - Leg kick/ front, side, round kick to the opponents's knee or thigh;

3 - Using distance and angle to manage your selection of techniques and movement (punches, kicks, throws, and finishing techniques)

You will see these combative principles applied over, and over again in MMA bouts today because they are timeless components of unarmed combat. Although we all like to think we are somehow greater than the next guy, we need to reflect on the purposes of the application (self-defense/LEO/military/ tournament, etc...) and work within its boundaries/ rules.

by Renshi D. Hassin and Kyoshi S. Sherbourne (2016)

The origins of Karate and our lineage...

Karate 空手; Japanese pronunciation is a martial art developed on the Ryukyu Islands in what is now Okinawa, Japan. It developed from the indigenous martial arts of the Ryukyu Islands: called te 手, literally meaning "hand"; tii in Okinawan under the influence of Chinese martial arts, particularly Fujian White Crane. Karate is now predominantly a striking art using punching, kicking, knee and elbow strikes, and open hand techniques such as knife-hand, spear-hand, and palm-heel strikes. Historically and in some modern styles grappling, throws, joint locks, restraints, and vital point strikes are also included. A karate practitioner is called a karate-ka (空手家).

The origins and influences that contributed to current traditional Okinawan Karate and Kobudo stem back approximately 1000 years to the time of the Bodhidarma. A very detailed article which outlines the general development of Karate from this time period forward can be viewed at http://karatevid.com/content/article-history.htm

Karate eventually developed in the Ryukyu Kingdom around the late 1300's to early 1400's . Through various Chinese and Japanese occupations Karate evolved in Okinawa as a distinct martial art. The influences of Zen and Buddhism fostered discipline and the indomitable spirit of the Karate-ka. Karate was brought to the Japanese mainland in the early 20th century during a time of cultural exchanges between the Japanese and the Chinese. It was systematically taught in Japan. In 1922 the Japanese Ministry of Education invited Gichin Funakoshi to Tokyo to give a karate demonstration. In 1924 Keio University established the first university karate club in mainland Japan and by 1932, many major Japanese universities had karate clubs. In this era of escalating Japanese militarism, the name was changed from 唐手 ("Chinese hand" or "Tang hand") to 空手 ("empty hand") – both of which are pronounced karate – to indicate that the Japanese wished to develop the combat form in Japanese style. After World War II, Okinawa became an important United States military base and karate became popular among servicemen stationed there.

Sherbourne Martial Arts Karate lessons and Kobudo is directly from Okinawa...

Master Shigeru Nakamura 1893 - 1969: (Master Seikichi Odo's Main Karate Instructor):

Master Nakamura lived in the City of Nago. His first introduction to karate was at the Icchu Middle School, in Shuri, Okinawa. His instructors included Kanryo Higashionna, Kentsu Yabu & Chomo Hanashiro. Yastune Itosu also made periodic visits to the school. After graduating from the middle school, Nakamura returned to Nago, where he continued learning Karate under Shinkichi Kunioshi, the successor to the legendary Naha "Bushi" Sakiyama. Shigeru Nakamura established his own dojo in Nago City in 1953.

The "Okinawa Kenpo Renmei" was formed by Zenryo Shimabuku and Shigeru Nakamura in 1955, with Nakamura as President. Master Nakamura was known for developing full contact sparring using "Bogu Gear".

Master Seikichi Odo 1926 - 2002: (Simon Sherbourne's Main Karate & Kobudo Instructor)

Seikichi Odo was appointed Master of Okinawa Kenpo Karate after the death of Master Nakamura in 1969. Seikichi Odo was also recognized as the President of the All Okinawa Kenpo Karate-do League. This is when Master Odo added the weapons/kobudo to Okinawa Kenpo, and coined the new style: "Okinawa Kenpo Karate-Kobudo". Please see the Kobudo page for details about our Kobudo training.

Master Odo was ranked 9th Dan when is passed in 2002. His Karate and Kobudo will live on through his students who continue to practice and teach his ways. Odo Sensei is remembered throughout the world as a top quality teacher and practitioner. Hanshi Seikichi Odo, was the Head of the Ryukyu Hon Kenpo Kobujutsu Federation and passed without a successor. A list of the Dojo Heads directly under Seikichi Odo at the time of his death can be seen at the RHKKF website.

Choki Motobu and his views on Karate

Many think of him as a bad-ass (and for his time, he certainly was), but if you read his teachings it shows that he was dealing with the same noise over 100 years ago that we are dealing with today – and this is obvious in a great quote from Motobu: “Nothing is more harmful to the world than a martial art that is not effective in actual self-defense.” He was facing the same issues and dealing with the same types ineffective martial arts driven by ego rather than effectiveness that we deal with today. So he chose to challenge and test his technique, and his conclusions led him to take it back to simplicity – he stated many times that Naihanchi kata has everything a person needs to know (he viewed this Kata as a complete system of self-defense that could be studied for years). Despite what people think, Motobu did learn other Kata, but he chose to focus on Niahanchi sho-dan as his primary training tool – it was simple, brutal, effective, and it contains all of the key combative techniques in your list below.

Sherbourne's Discussions with a couple Karate Masters on the subject...

During my training with Hanshi Seikichi Odo (1987 to 2002) I asked these questions and Odo Sensei explained that all the existing upper ranks in Okinawa viewed karate as one complete martial art. He inferred to me that it was ego that spawned the birth of so many different styles, and that this was not in keeping with being a selfless Budo-ka/ Karate-ka.

I asked Seiki Toma (in 2002) the same question as to where did all the different styles of karate come from... He chuckled a little and said when he was a young man, all these different styles (Shotokan, Goju Ryu, Shito Ryu, Isshin Ryu, Kyokushin, Shorin Ryu... etc.) did not exist. Karate was just karate, and everyone on the Island (Okinawa) trained together and shared their practices with each other.

This perepective on training is far from the current state of karate practice that separates practitioners by style and variations of practice. Training for tournaments also causes practitioners to cator to the rules for scoring and defending, instead of training for the purposes of life threatening circumstances.

However, in traditional styles there still exist some fundamental combatives principles that transcend style:

1 - The “One Punch Finish” is a reality with proper karate training (Makiwara, etc.);

2 - Leg kick/ front, side, round kick to the opponents's knee or thigh;

3 - Using distance and angle to manage your selection of techniques and movement (punches, kicks, throws, and finishing techniques)

You will see these combative principles applied over, and over again in MMA bouts today because they are timeless components of unarmed combat. Although we all like to think we are somehow greater than the next guy, we need to reflect on the purposes of the application (self-defense/LEO/military/ tournament, etc...) and work within its boundaries/ rules.

by Renshi D. Hassin and Kyoshi S. Sherbourne (2016)

The origins of Karate and our lineage...

Karate 空手; Japanese pronunciation is a martial art developed on the Ryukyu Islands in what is now Okinawa, Japan. It developed from the indigenous martial arts of the Ryukyu Islands: called te 手, literally meaning "hand"; tii in Okinawan under the influence of Chinese martial arts, particularly Fujian White Crane. Karate is now predominantly a striking art using punching, kicking, knee and elbow strikes, and open hand techniques such as knife-hand, spear-hand, and palm-heel strikes. Historically and in some modern styles grappling, throws, joint locks, restraints, and vital point strikes are also included. A karate practitioner is called a karate-ka (空手家).

The origins and influences that contributed to current traditional Okinawan Karate and Kobudo stem back approximately 1000 years to the time of the Bodhidarma. A very detailed article which outlines the general development of Karate from this time period forward can be viewed at http://karatevid.com/content/article-history.htm

Karate eventually developed in the Ryukyu Kingdom around the late 1300's to early 1400's . Through various Chinese and Japanese occupations Karate evolved in Okinawa as a distinct martial art. The influences of Zen and Buddhism fostered discipline and the indomitable spirit of the Karate-ka. Karate was brought to the Japanese mainland in the early 20th century during a time of cultural exchanges between the Japanese and the Chinese. It was systematically taught in Japan. In 1922 the Japanese Ministry of Education invited Gichin Funakoshi to Tokyo to give a karate demonstration. In 1924 Keio University established the first university karate club in mainland Japan and by 1932, many major Japanese universities had karate clubs. In this era of escalating Japanese militarism, the name was changed from 唐手 ("Chinese hand" or "Tang hand") to 空手 ("empty hand") – both of which are pronounced karate – to indicate that the Japanese wished to develop the combat form in Japanese style. After World War II, Okinawa became an important United States military base and karate became popular among servicemen stationed there.

Sherbourne Martial Arts Karate lessons and Kobudo is directly from Okinawa...

Master Shigeru Nakamura 1893 - 1969: (Master Seikichi Odo's Main Karate Instructor):

Master Nakamura lived in the City of Nago. His first introduction to karate was at the Icchu Middle School, in Shuri, Okinawa. His instructors included Kanryo Higashionna, Kentsu Yabu & Chomo Hanashiro. Yastune Itosu also made periodic visits to the school. After graduating from the middle school, Nakamura returned to Nago, where he continued learning Karate under Shinkichi Kunioshi, the successor to the legendary Naha "Bushi" Sakiyama. Shigeru Nakamura established his own dojo in Nago City in 1953.

The "Okinawa Kenpo Renmei" was formed by Zenryo Shimabuku and Shigeru Nakamura in 1955, with Nakamura as President. Master Nakamura was known for developing full contact sparring using "Bogu Gear".

Master Seikichi Odo 1926 - 2002: (Simon Sherbourne's Main Karate & Kobudo Instructor)

Seikichi Odo was appointed Master of Okinawa Kenpo Karate after the death of Master Nakamura in 1969. Seikichi Odo was also recognized as the President of the All Okinawa Kenpo Karate-do League. This is when Master Odo added the weapons/kobudo to Okinawa Kenpo, and coined the new style: "Okinawa Kenpo Karate-Kobudo". Please see the Kobudo page for details about our Kobudo training.

Master Odo was ranked 9th Dan when is passed in 2002. His Karate and Kobudo will live on through his students who continue to practice and teach his ways. Odo Sensei is remembered throughout the world as a top quality teacher and practitioner. Hanshi Seikichi Odo, was the Head of the Ryukyu Hon Kenpo Kobujutsu Federation and passed without a successor. A list of the Dojo Heads directly under Seikichi Odo at the time of his death can be seen at the RHKKF website.

The History of Karate Belts and Ranks by Wendell E. Wilson (2010)

Introduction

Modern-day students of karate generally assume that the ranking system of kyu (color belt) and dan (black belt) levels, and the various titles that high-ranking black belts hold, are, like the katas, a part of karate tradition extending back centuries. However, despite the fact that karate is indeed very old, the ranking system itself dates back only to the early 20th century. A look at the history and development of the current rank system will help us to put our own belt ranks in proper historical perspective.

Japanese Martial Culture

Japanese culture tends to be highly regimented and structured. Virtually any traditional art that you might wish to study in Japan, from flower arranging (ikebana) to calligraphy (shodo), comes with its own progressive series of formal ranks. So it is also with the martial arts. Some early Japanese martial arts utilized a three-rank system which involved the awarding of certificates. The first, shodan, signified a beginner; the second, chudan, indicated middle rank; and the third, jodan, or upper rank, allowed the student to enter into the okuden, or secret traditions, of his school or style. Another early system utilized a series of licenses called menkyo. The first rank, kirikami, was usually awarded after one to three years of training, and signified that the student had been accepted by his school as a serious practitioner. After three to five more years the student was presented with a mokuroku, or written catalog of the system’s techniques. After two to ten more years the student finally received his menkyo, or license to teach. The menkyo might also specify one of several different possible titles indicating his position with the system’s organizational structure. The ultimate certificate was the menkyo kaiden, awarded to students who had mastered every aspect of the system. Some system headmasters awarded only a single menkyo kaiden in their lifetime, to the person they chose as their successor.

Okinawan Martial Culture

Karate, however, is of Okinawan origin rather than Japanese. The early Okinawans had existed for centuries under Chinese hegemony, gradually assimilating aspects of 1 Chinese hard-style kung fu into their indigenous fighting style (called simply te, or “hand” fighting). Chinese empty-hand fighting had evolved as part of the Buddhist monastic tradition. Karate in Okinawa was passed on privately within families, from father to son, and was taught to members of the aristocracy and the police force to help guarantee control over the general populace. Oftentimes, especially under Japanese occupation when the teaching of martial skills was prohibited, the training was carried out in secret, after dark, in enclosed private courtyards. Masters would select only a few students to teach, and charged no fee. A student’s progress was measured not by an assigned rank but by how many years he had studied, how much he had learned, and how well his character had developed. Nothing more.

Origin of the Color-Belt System

Speculative tradition proposes that belt colors (as indicators of rank) originated in a peculiar habit of washing all of one’s training clothes except the cloth belt. Thus as training progressed the initially white belt would first turn a dingy yellow, then a greenish yellow-brown, then a really dirty brown, and finally a repulsively filthy black. Eventually, so they say, this progression was formalized as the white, yellow, green, brown and black belt ranks. Well, it’s a nice story, but probably not true. Even so, some modern karate practitioners do not wash their belts, hoping to achieve a worn and rugged look as evidence of their years of hard training. Others overwash their belts to get them looking worn-out sooner. And still others prefer to wear a new-looking belt at all times. It’s a matter of personal preference. In some rare cases a master will present his old and frayed black belt to his favorite student or successor, who will preserve it as a treasured memento and wear it as an emblem of pride and honor to his teacher. Although not traditional in Shuri-ryu, some schools encourage black belt holders to have their name (and perhaps also the name of their style) embroidered in gold Japanese characters on the end-lengths of their belt. The kyu/dan system of rankings was actually devised around the turn of the century by a Japanese martial artist, Jigoro Kano (1860-1938). Kano had taken the samurai battlefield art of jujitsu or aikijutsu and modified it heavily so as to eliminate the really dangerous aspects and make it safe for practice as a sport. This new sport, judo, he introduced into Japanese grade schools and colleges. With so many new students, all in the highly structured public school environment, he decided that a grading and ranking system would help to encourage them, and would allow them to gauge their own progress. There had always been interest in Okinawan fighting arts among the Japanese, but the Okinawans had long considered the Japanese to be foreign invaders and were not about to teach them all of their fighting secrets. Finally, however, karate came out of the closet when Anko Itosu (1830-1915) shocked the Okinawan martial arts community by initiating a program to teach karate to children in Okinawan public schools in 1901. Shortly thereafter, an Okinawan master named Gichin Funakoshi (1868-1957), a student of Itosu, decided it was time to bring a form of karate to Japan. He merged selected elements and modified selected katas from various Okinawan systems into a new style for “export” which came to be called shotokan (his nickname was “Shoto”). His purpose was to provide good exercise and character-building training for the Japanese (I guess he 2 figured they needed it), not to teach them how to beat up Okinawans. So in formulating his new style he altered many of the katas and techniques in terms of their practical fighting value, rendered them more defensive rather than offensive, eliminated entirely the kyusho-jitsu or nerve-striking training which Okinawan masters considered most dangerous and secret, and he also eliminated all use of held-held weapons. (Even today, shotokan tournaments have no weapons divisions.) Funakoshi moved more or less permanently to Japan where he instituted karate training in 1922, and soon it spread to schools as the practice of judo had done. Funakoshi became closely associated with the aristocratic Jigoro Kano, and by the late 1930’s he had developed the modern karate uniform or gi as a lighter-weight version of Kano’s judo gi. He eventually decided that it would be appropriate to adopt the colorbelt system for bestowing karate ranks on his students; this system was by then well established in Japanese martial arts, under the aegis of the Japanese Butoku-kai, the section of the Ministry of Education which was established in 1895 to oversee ranks and standards for kendo and judo. In 1903-1906 the Butoku-kai first bestowed the samurai titles of hanshi and kyoshi (what amounted to instructors’ licenses) on several kendo specialists; the title of renshi (a training apprentice) was added later. The belt-rank system devised by Kano and accepted by the Butoku-kai consisted of six kyu (color-belt) grades, three white and three brown, and ten dan (black belt) grades. Funakoshi adopted this same system for karate after 1922, and on April 12, 1924, he awarded the first karate black belts and dan rankings to seven of his students: Hironori Ohtsuka (later the founder of Wado-ryu), Shinken Gima, Ante Tokuda, and four others named Katsuya, Akiba, Shimizu, and Hirose. At the time, Funakoshi himself held no rank in any martial art or system.

Standardizing Rank Requirements

In 1938 the Butoku-kai called upon all existing karate schools and styles to register for official sanctioning, and an important meeting was called for the purpose of standardizing rank requirements (something that had never been done!). Thus the various Japanese styles (Wado-ryu, Shito-ryu, Kushin-ryu, Japanese Kempo, Shindo-jinen-ryu, Gojo-ryu and Shotokan) were brought together under a single set of grading standards. Ironically, Funakoshi was awarded his renshi title by the board of the Butoku-kai, on which sat one of his own students, Koyu Konishi (who was Japanese by birth, an advantage the Okinawan Funakoshi did not share). Chojun Miyagi (1888-1953), the Okinawan founder of Gojo-ryu, was the first karate recipient of the title of kyoshi (master or “assistant professor”) from the Butoku-kai in 1937.

Post-War Organizations

World War II caused a major disruption in Japanese and Okinawan martial arts. Many masters had died during the war, the practice of martial arts was forbidden for a time by the American occupying forces, and the Butoku-kai was shut down. Each school was on its own, and the surviving leaders had to begin anew. In Okinawa the kyu/dan system was not yet well established, although some systems utilized at least the black belt. Following the war it finally became more widely accepted, leaving the problem of developing new sanctioning bodies to legitimize the ranks being awarded. 3 During the early 1950’s certification was accomplished through associations formed by the dojos in each style, including the Goju-kai, Shito-kai, Chito-kai, Shotokai, and the Japan Karate Association. Each formed a board and designated an officer who would have signature authority on rank certificates. Those recipients reaching a high dan ranking often went out and started their own new styles. These groups usually cited affiliation to some higher authority or granting agency to legitimize their actions; the Japanese Ministry of Education was a favorite. Other new associations sprang up in Japan and Okinawa, becoming the ranking authorities for grantors as the Butoku-kai had been. High officers in these organizations usually assumed a rank for themselves based on criteria they had written. Among the earliest was the All-Japan Karatedo Federation, initiated shortly after World War II by such headmasters as Funakoshi, Tsuyoshi Chitose (born in 1898 and still President as of 1993), Kenwa Mabuni, Gogen Yamaguchi and Kanken Toyama. The International Martial Arts Federation, launched in 1952, included judo and kendo as well as karatedo. It established a system involving ten black belt levels plus the titles of renshi, kyoshi and hanshi; many of the highest ranked modern masters received their ranks through this organization. In Okinawa the kyu/dan system did not really become universal until 1956, when the Okinawa Karate Federation was formed. Chosin Chibana (founder of Shorin-ryu) was the first president; Chibana and Kanken Toyama were officially recognized by the Japanese Ministry of Education to grant any rank in any style of karate. This helped to end the Japanese discrimination against Okinawans in the granting of ranks and titles. For some years previous, the principle “system” used in Okinawa had simply been white belt for students and black belt for teachers. In 1964 an organization arose which for the first time unified all existing styles of karate: the Federation of All-Japan Karatedo Organizations (FAJKO). The ranking standards set forth by FAJKO in 1971 ultimately became recognized by the International Traditional Karate Federation (ITKF) and are generally accepted worldwide. It includes only six color-belt levels; some systems add two to four more and the exact sequence of colors tends to vary from one style to another. But today essentially all karate systems, whether formally tied to FAJKO or not, conform more or less to the basic FAJKO criteria and standards. This includes the All-Okinawa Karate and Kobudo Rengokai (AOKKR, formed in 1967). In the United States the principle certifying organization for Okinawan, Japanese and Korean karate was, for a long time, Robert Trais’s U.S. Karate Association. This organization in the 1980’s boasted a membership of 425 American and 86 foreign karate schools in 56 countries. During its entire history it represented over 800,000 members. Following Trias’s death in 1989, the association disbanded into four smaller organizations. KoSho Shuri-ryu schools are now in the U.S.A. Karate Federation, formed in 1985, which became a member of the U.S. Olympic Committee, the PanAmerican Union of Karatedo Organizations (PUKO) and the World Union of Karatedo Organizations (WUKO; now reorganized as the World Karate-do Federation). As of 1996 it represents about 15,000 karate practitioners. The current president of the USAKF, Hanshi George Anderson (10th dan), is also Director of Kwanmuzendokai International; both organizations currently underwrite and certify our rank certificates, 4 5 and Hanshi Anderson is the sensei of Shihan John Linebarger, Director of KoSho Karate and Chief Instructor of Robert Trias’s Shuri-ryu in Arizona.

Conclusion

Karate ranks are thus, historically, a rather modern construct imposed over an old martial art. They are important in the standardization of requirements which helps to maintain the integrity and value of systems based on tradition. However, it should never be forgotten that rank does not make the man. Within every rank there can be found a wide range of students whose skills vary dramatically, causing the observant karateka to sometimes wonder whether rank really guarantees much of anything. Achievement of rank should be considered as a side-effect of karate training and not a goal. The true goal is personal development, to “be all that we can be” at whatever rank level we may attain.

References

ANDERSON, G.E. (1994) An overview of the belt system. Handout, International Bujitsu Development and Research Foundation, Tucson Seminar, October 9, 1994, p. 8-9. CORCORAN, J., and FARKAS, E. (1993) The Original Martial Arts Encyclopedia. Pro-Action Publishing, Los Angeles, 437 p. DAY, J. (1993) The tradition of pride and humility. Dojo magazine, Spring 1993, p. 67- 70. DURBIN, W. (1995) The puzzling maze of ranks and titles: Shihan, Sensei, Soke, Shodan—what does it all mean? Black Belt magazine, vol. 33, no. 11 (November), p. 30-33, 134-135, 140. HURST, G.C. III (1995) Ryuha in the martial and other Japanese arts. Journal of Asian Martial Arts, 4 (4), 12-25. KIM, R. (1993) Tradition, standards, discipline. Dojo magazine, Fall 1993, p. 6-10. SELLS, J. (1994) Karate-do and the black belt; how the masters got their ranks. Dojo magazine, Winter 1994, p. 14-19. SELLS, J. (1995) Unante, The Secrets of Karate. Rank Designation Requirements,

Privately published. ©Wendell E. Wilson (2010) (email: minrecord@comcast.net) from Essays on the Martial Arts Home: http://www.mineralogicalrecord.com/wilson/karate.asp

Modern-day students of karate generally assume that the ranking system of kyu (color belt) and dan (black belt) levels, and the various titles that high-ranking black belts hold, are, like the katas, a part of karate tradition extending back centuries. However, despite the fact that karate is indeed very old, the ranking system itself dates back only to the early 20th century. A look at the history and development of the current rank system will help us to put our own belt ranks in proper historical perspective.

Japanese Martial Culture

Japanese culture tends to be highly regimented and structured. Virtually any traditional art that you might wish to study in Japan, from flower arranging (ikebana) to calligraphy (shodo), comes with its own progressive series of formal ranks. So it is also with the martial arts. Some early Japanese martial arts utilized a three-rank system which involved the awarding of certificates. The first, shodan, signified a beginner; the second, chudan, indicated middle rank; and the third, jodan, or upper rank, allowed the student to enter into the okuden, or secret traditions, of his school or style. Another early system utilized a series of licenses called menkyo. The first rank, kirikami, was usually awarded after one to three years of training, and signified that the student had been accepted by his school as a serious practitioner. After three to five more years the student was presented with a mokuroku, or written catalog of the system’s techniques. After two to ten more years the student finally received his menkyo, or license to teach. The menkyo might also specify one of several different possible titles indicating his position with the system’s organizational structure. The ultimate certificate was the menkyo kaiden, awarded to students who had mastered every aspect of the system. Some system headmasters awarded only a single menkyo kaiden in their lifetime, to the person they chose as their successor.

Okinawan Martial Culture

Karate, however, is of Okinawan origin rather than Japanese. The early Okinawans had existed for centuries under Chinese hegemony, gradually assimilating aspects of 1 Chinese hard-style kung fu into their indigenous fighting style (called simply te, or “hand” fighting). Chinese empty-hand fighting had evolved as part of the Buddhist monastic tradition. Karate in Okinawa was passed on privately within families, from father to son, and was taught to members of the aristocracy and the police force to help guarantee control over the general populace. Oftentimes, especially under Japanese occupation when the teaching of martial skills was prohibited, the training was carried out in secret, after dark, in enclosed private courtyards. Masters would select only a few students to teach, and charged no fee. A student’s progress was measured not by an assigned rank but by how many years he had studied, how much he had learned, and how well his character had developed. Nothing more.

Origin of the Color-Belt System

Speculative tradition proposes that belt colors (as indicators of rank) originated in a peculiar habit of washing all of one’s training clothes except the cloth belt. Thus as training progressed the initially white belt would first turn a dingy yellow, then a greenish yellow-brown, then a really dirty brown, and finally a repulsively filthy black. Eventually, so they say, this progression was formalized as the white, yellow, green, brown and black belt ranks. Well, it’s a nice story, but probably not true. Even so, some modern karate practitioners do not wash their belts, hoping to achieve a worn and rugged look as evidence of their years of hard training. Others overwash their belts to get them looking worn-out sooner. And still others prefer to wear a new-looking belt at all times. It’s a matter of personal preference. In some rare cases a master will present his old and frayed black belt to his favorite student or successor, who will preserve it as a treasured memento and wear it as an emblem of pride and honor to his teacher. Although not traditional in Shuri-ryu, some schools encourage black belt holders to have their name (and perhaps also the name of their style) embroidered in gold Japanese characters on the end-lengths of their belt. The kyu/dan system of rankings was actually devised around the turn of the century by a Japanese martial artist, Jigoro Kano (1860-1938). Kano had taken the samurai battlefield art of jujitsu or aikijutsu and modified it heavily so as to eliminate the really dangerous aspects and make it safe for practice as a sport. This new sport, judo, he introduced into Japanese grade schools and colleges. With so many new students, all in the highly structured public school environment, he decided that a grading and ranking system would help to encourage them, and would allow them to gauge their own progress. There had always been interest in Okinawan fighting arts among the Japanese, but the Okinawans had long considered the Japanese to be foreign invaders and were not about to teach them all of their fighting secrets. Finally, however, karate came out of the closet when Anko Itosu (1830-1915) shocked the Okinawan martial arts community by initiating a program to teach karate to children in Okinawan public schools in 1901. Shortly thereafter, an Okinawan master named Gichin Funakoshi (1868-1957), a student of Itosu, decided it was time to bring a form of karate to Japan. He merged selected elements and modified selected katas from various Okinawan systems into a new style for “export” which came to be called shotokan (his nickname was “Shoto”). His purpose was to provide good exercise and character-building training for the Japanese (I guess he 2 figured they needed it), not to teach them how to beat up Okinawans. So in formulating his new style he altered many of the katas and techniques in terms of their practical fighting value, rendered them more defensive rather than offensive, eliminated entirely the kyusho-jitsu or nerve-striking training which Okinawan masters considered most dangerous and secret, and he also eliminated all use of held-held weapons. (Even today, shotokan tournaments have no weapons divisions.) Funakoshi moved more or less permanently to Japan where he instituted karate training in 1922, and soon it spread to schools as the practice of judo had done. Funakoshi became closely associated with the aristocratic Jigoro Kano, and by the late 1930’s he had developed the modern karate uniform or gi as a lighter-weight version of Kano’s judo gi. He eventually decided that it would be appropriate to adopt the colorbelt system for bestowing karate ranks on his students; this system was by then well established in Japanese martial arts, under the aegis of the Japanese Butoku-kai, the section of the Ministry of Education which was established in 1895 to oversee ranks and standards for kendo and judo. In 1903-1906 the Butoku-kai first bestowed the samurai titles of hanshi and kyoshi (what amounted to instructors’ licenses) on several kendo specialists; the title of renshi (a training apprentice) was added later. The belt-rank system devised by Kano and accepted by the Butoku-kai consisted of six kyu (color-belt) grades, three white and three brown, and ten dan (black belt) grades. Funakoshi adopted this same system for karate after 1922, and on April 12, 1924, he awarded the first karate black belts and dan rankings to seven of his students: Hironori Ohtsuka (later the founder of Wado-ryu), Shinken Gima, Ante Tokuda, and four others named Katsuya, Akiba, Shimizu, and Hirose. At the time, Funakoshi himself held no rank in any martial art or system.

Standardizing Rank Requirements

In 1938 the Butoku-kai called upon all existing karate schools and styles to register for official sanctioning, and an important meeting was called for the purpose of standardizing rank requirements (something that had never been done!). Thus the various Japanese styles (Wado-ryu, Shito-ryu, Kushin-ryu, Japanese Kempo, Shindo-jinen-ryu, Gojo-ryu and Shotokan) were brought together under a single set of grading standards. Ironically, Funakoshi was awarded his renshi title by the board of the Butoku-kai, on which sat one of his own students, Koyu Konishi (who was Japanese by birth, an advantage the Okinawan Funakoshi did not share). Chojun Miyagi (1888-1953), the Okinawan founder of Gojo-ryu, was the first karate recipient of the title of kyoshi (master or “assistant professor”) from the Butoku-kai in 1937.

Post-War Organizations

World War II caused a major disruption in Japanese and Okinawan martial arts. Many masters had died during the war, the practice of martial arts was forbidden for a time by the American occupying forces, and the Butoku-kai was shut down. Each school was on its own, and the surviving leaders had to begin anew. In Okinawa the kyu/dan system was not yet well established, although some systems utilized at least the black belt. Following the war it finally became more widely accepted, leaving the problem of developing new sanctioning bodies to legitimize the ranks being awarded. 3 During the early 1950’s certification was accomplished through associations formed by the dojos in each style, including the Goju-kai, Shito-kai, Chito-kai, Shotokai, and the Japan Karate Association. Each formed a board and designated an officer who would have signature authority on rank certificates. Those recipients reaching a high dan ranking often went out and started their own new styles. These groups usually cited affiliation to some higher authority or granting agency to legitimize their actions; the Japanese Ministry of Education was a favorite. Other new associations sprang up in Japan and Okinawa, becoming the ranking authorities for grantors as the Butoku-kai had been. High officers in these organizations usually assumed a rank for themselves based on criteria they had written. Among the earliest was the All-Japan Karatedo Federation, initiated shortly after World War II by such headmasters as Funakoshi, Tsuyoshi Chitose (born in 1898 and still President as of 1993), Kenwa Mabuni, Gogen Yamaguchi and Kanken Toyama. The International Martial Arts Federation, launched in 1952, included judo and kendo as well as karatedo. It established a system involving ten black belt levels plus the titles of renshi, kyoshi and hanshi; many of the highest ranked modern masters received their ranks through this organization. In Okinawa the kyu/dan system did not really become universal until 1956, when the Okinawa Karate Federation was formed. Chosin Chibana (founder of Shorin-ryu) was the first president; Chibana and Kanken Toyama were officially recognized by the Japanese Ministry of Education to grant any rank in any style of karate. This helped to end the Japanese discrimination against Okinawans in the granting of ranks and titles. For some years previous, the principle “system” used in Okinawa had simply been white belt for students and black belt for teachers. In 1964 an organization arose which for the first time unified all existing styles of karate: the Federation of All-Japan Karatedo Organizations (FAJKO). The ranking standards set forth by FAJKO in 1971 ultimately became recognized by the International Traditional Karate Federation (ITKF) and are generally accepted worldwide. It includes only six color-belt levels; some systems add two to four more and the exact sequence of colors tends to vary from one style to another. But today essentially all karate systems, whether formally tied to FAJKO or not, conform more or less to the basic FAJKO criteria and standards. This includes the All-Okinawa Karate and Kobudo Rengokai (AOKKR, formed in 1967). In the United States the principle certifying organization for Okinawan, Japanese and Korean karate was, for a long time, Robert Trais’s U.S. Karate Association. This organization in the 1980’s boasted a membership of 425 American and 86 foreign karate schools in 56 countries. During its entire history it represented over 800,000 members. Following Trias’s death in 1989, the association disbanded into four smaller organizations. KoSho Shuri-ryu schools are now in the U.S.A. Karate Federation, formed in 1985, which became a member of the U.S. Olympic Committee, the PanAmerican Union of Karatedo Organizations (PUKO) and the World Union of Karatedo Organizations (WUKO; now reorganized as the World Karate-do Federation). As of 1996 it represents about 15,000 karate practitioners. The current president of the USAKF, Hanshi George Anderson (10th dan), is also Director of Kwanmuzendokai International; both organizations currently underwrite and certify our rank certificates, 4 5 and Hanshi Anderson is the sensei of Shihan John Linebarger, Director of KoSho Karate and Chief Instructor of Robert Trias’s Shuri-ryu in Arizona.

Conclusion

Karate ranks are thus, historically, a rather modern construct imposed over an old martial art. They are important in the standardization of requirements which helps to maintain the integrity and value of systems based on tradition. However, it should never be forgotten that rank does not make the man. Within every rank there can be found a wide range of students whose skills vary dramatically, causing the observant karateka to sometimes wonder whether rank really guarantees much of anything. Achievement of rank should be considered as a side-effect of karate training and not a goal. The true goal is personal development, to “be all that we can be” at whatever rank level we may attain.

References

ANDERSON, G.E. (1994) An overview of the belt system. Handout, International Bujitsu Development and Research Foundation, Tucson Seminar, October 9, 1994, p. 8-9. CORCORAN, J., and FARKAS, E. (1993) The Original Martial Arts Encyclopedia. Pro-Action Publishing, Los Angeles, 437 p. DAY, J. (1993) The tradition of pride and humility. Dojo magazine, Spring 1993, p. 67- 70. DURBIN, W. (1995) The puzzling maze of ranks and titles: Shihan, Sensei, Soke, Shodan—what does it all mean? Black Belt magazine, vol. 33, no. 11 (November), p. 30-33, 134-135, 140. HURST, G.C. III (1995) Ryuha in the martial and other Japanese arts. Journal of Asian Martial Arts, 4 (4), 12-25. KIM, R. (1993) Tradition, standards, discipline. Dojo magazine, Fall 1993, p. 6-10. SELLS, J. (1994) Karate-do and the black belt; how the masters got their ranks. Dojo magazine, Winter 1994, p. 14-19. SELLS, J. (1995) Unante, The Secrets of Karate. Rank Designation Requirements,

Privately published. ©Wendell E. Wilson (2010) (email: minrecord@comcast.net) from Essays on the Martial Arts Home: http://www.mineralogicalrecord.com/wilson/karate.asp

Contact Us

Address :

1959 Mallard Road - Unit 7 London ON N6H 5L8

Phone : 519-614-1167

Email :

wkkjo.budo@gmail.com

Quick Links

© 2022 All Right Reserved | World Karate Kobudo JiuJitsu Organization.

Website Design: Customer Contact Solutions